Published: October 25, 2024

Intersectionality and Disability in Higher Education Research

Intersectional Identity: More Than the Sum of Its Parts

Our individual identities – disability, gender, race, ethnicity, sexuality, place of origin, first-generation – are both separate and together in the complexity of who we are.

Intersectionality theory – grounded in the work of Kimberlé Crenshaw – helps to explain this complexity by emphasizing the compounding nature of oppression for people from multiple marginalized populations.

Intersectionality’s role in research on disability in postsecondary education is an opportunity to bring layers, nuance, and individual differences — a diversity that can be reflected in research aims, methods, interpretations of findings, and recommendations for policy and practice.

Address the Intersectional Experiences — Including Disability — of Your Study Population

Disability is not a“one-size-fits-all” experience as students navigate opportunities and obstacles on campus.

Their intersectional identities mean that there is great diversity within the disabled student experience – even beyond the many different kinds of apparent and non-apparent disabilities.

Ableism is embedded in many higher education policies and practices. To understand the disabled student experience, it is essential to also understand the intersectional experiences of ableism.

Photo by Chona Kasinger, Disabled And Here collection, used under Creative Commons Attribution License.

Consider Disability Disclosure (or Lack Thereof)

Critical student decisions about disclosing a disability and navigating accessibility are challenging in institutions largely designed without intersectionality in mind.

Choosing not to disclose a disability (and not to receive institutional supports or accommodations) can be a strategy they use to protect themselves against negative stereotypes, particularly perceptions of laziness and incompetence.

This strategic decision-making around disclosure leads to feelings of distress, isolation, and alienation. These contribute to disconnect and a lower rate of persistence to graduation.

Postsecondary Students and Their Disability Disclosure

Disclose to Instructor (Without Official Accommodation Letter)

Disclose to Instructor (With Official Accommodation Letter)

Disclose to Institution

Disclose to Peers

Source: National Disability Center for Student Success College Accessibility Measure Survey, 2024

Research Can Address Hidden Barriers to Inclusive Learning Environments

Feelings of exclusion and low expectations about their potential from both peers and faculty are more likely to be reported by disabled students with intersectional identities.

Social navigation is required to deal with differences in apparent and non-apparent disabilities, fluctuating conditions, and a wide variety of classroom settings and expectations — which opens up judgments based on race and gender (beyond disability).

Disabled students are often tasked with educating their peers on top of managing the discrimination of their intersectional identities. This is an additional burden of time and energy.

Researchers have the opportunity to explicitly investigate the postsecondary experiences of disabled students from diverse, intersectional identities. This is both an opportunity and a great responsibility.

Photo by Gritchelle Fallesgon, Disabled And Here collection, used under Creative Commons Attribution License.

Tips and Strategies for Researchers

Contributors

Coordinator of Student Partnerships

Doctoral Candidate in the Department of Educational Psychology | Human Development, Culture, and Learning Science

The University of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin

Recommended Citation

Lama, D. & Kafer, A. (2024). Intersectionality and Disability in Higher Education Research. National Disability Center for Student Success, The University of Texas at Austin. Funded by IES Cooperative Agreement #R324C230008.

Key References

Abrams, E. J., & Abes, E. S. (2021). “It’s Finding Peace in My Body”: Using Crip Theory to Understand Authenticity for a Queer, Disabled College Student. Journal of College Student Development, 62(3), 261-275.

Cech, E. A. (2023). Engineering ableism: The exclusion and devaluation of engineering students and professionals with physical disabilities and chronic and mental illness. Journal of Engineering Education, 112(3), 462-487.

Durodoye B. A., Combes B. H., Bryant R. M. (2004). Counselor intervention in the post-secondary planning of African American students with learning disabilities. Professional School Counseling, 7, 133–140.

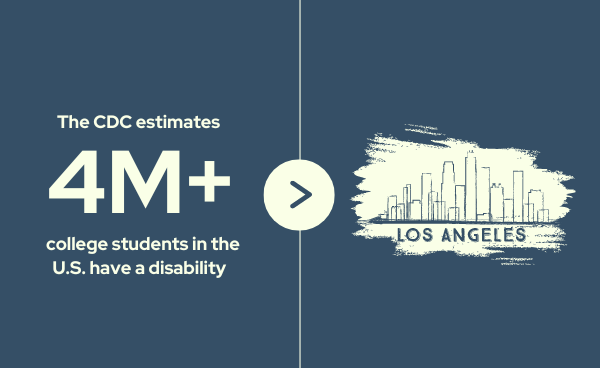

Mata, R.A. & Borrego, M. (2024). Disabled Students in U.S. Postsecondary Education. National Disability Center for Student Success, The University of Texas at Austin. Funded by IES Cooperative Agreement #R324C230008.

McDonald K. E., Keys C. B., Balcazar F. E. (2007). Disability, race/ethnicity and gender: Themes of cultural oppression, acts of individual resistance. American Journal of Community Psychology, 39, 145–161.

Miller, Ryan A. “‘Sometimes You Feel Invisible’: Performing Queer/Disabled in the University Classroom.” The Educational Forum (West Lafayette, Ind.) 79.4 (2015): 377–393.

Mireles, Danielle. “Theorizing Racist Ableism in Higher Education.” Teachers College Record 124.7 (2022): 17–50.